Panic in London? The attitudes of the civilian population to air attack in 1917/18 and in 1944/45

Aerial warfare in the 20th century

The two world wars of the 20th century introduced the world, and Britain, to the concept of total war. A major aspect of which was the development of air power and the use of aerial bombardment on major cities. This article contains two snap shots of the effects of aerial warfare on what was then one of the biggest urban and commercial centres in the world, London.

Bombing London Gothas & V2 Rockets

The bombing attacks on London by German Gotha bombers in 1917 and by V2 Rockets in 1944/45 came as the population of London had just heaved a sigh of relief at the cessation of Zeppelin raids and V1 flying bombs respectively. 1917 and the Autumn / Spring of 1944/45 had been periods of time when the morale of the civilians of Britain, especially London were severely strained. The attacks of the Gotha bombers, with their plan to ‘set London on fire’ and the revenge attacks of the V 2 rockets or Vergeltungswaffe (retribution weapon) were to severely strain the resources, reactions and the government and the city of London, showing the effects of total warfare could have on urban morale and physical city landscapes.

Gothas raid London

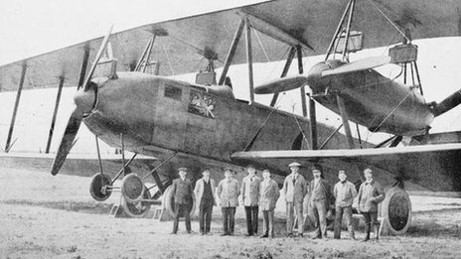

By the Spring of 1917, 23 Gotha bombers were in service, with more on the production line. The two engine bi-plane had a wing span of 72 feet and a payload of 13 bombs, seven of 50 kilos and six of 12.5. The German air force soon worked out that the best results could be achieved from bombing in daylight from a great height. The RNAS and RCF planes could not fly high enough to effectively defend against the Gothas. One of the worst raids came on Wednesday 13 June 1917, when a bomb dropped through the roof of the Upper North Street LCC school, passing through the girls’ department on the top floor, through the boys’ department and exploding in the basement, where all in the infants’ department were killed, except the teacher. A total of 18 children were killed and 34 injured. In the same raid, at Liverpool station 16 died, and at Fenchurch Street station 19 were killed.

Blow to morale

A raid on 7 July was a blow to the morale of the population of London as in broad daylight 20 or more Gothas were watched as they approached London, undeterred by any air defence. It was only when the anti-aircraft guns in London’s parks began to fire that people began to take cover. In that raid 53 people died and 183 were injured. The damage to property had doubled from that of 13 June, being estimated at £200,000.

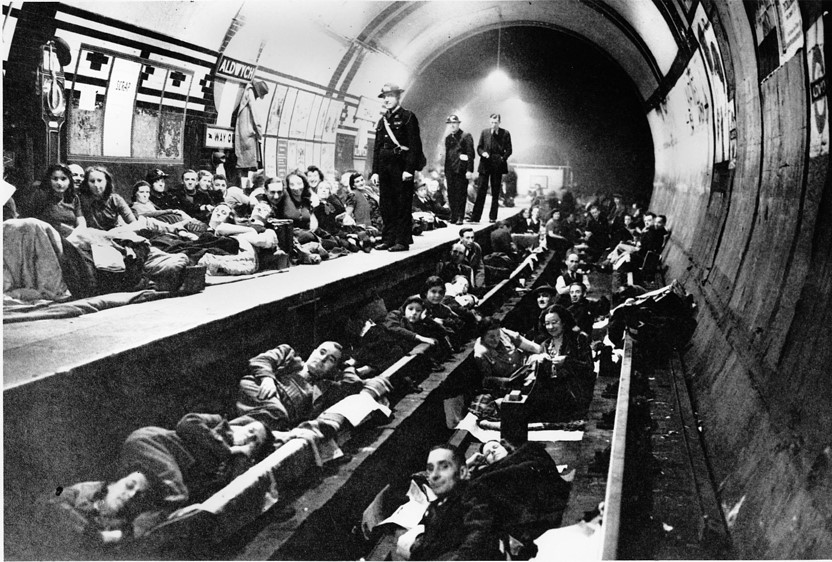

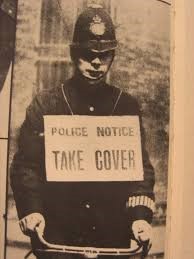

In addition to this apparent ease with which the Gothas were bombing the city to the refusal of the authorities to give adequate air raid warnings was resented by Londoners. Sir George Cave announced in parliament on 28 June that it was “Neither practicable or desirable to give warnings”, but changed his mind after 5 July raid. Daytime warnings were to be based on maroons being fired from some fire and police stations with policemen riding around with ‘take cover’ notices. The confusion and inadequacy of night time air raid warnings was particularly resented in the ‘Harvest Moon’ night time raids beginning 24 September – 1 October. This had still not been resolved by January 1918 as a letter to The Times from a local vicar pleaded: “London has not lost its nerve and all we ask for is a definite clear, audible warning at all hours when a raid is impending.” The Londoners took shelter increasingly in the tube stations, whether there was a raid or not, and during the week of the ‘Harvest Moon’ raids many left the city for the night to take shelter in the surrounding countryside.

The strategy of repeated bombing night after night was according to Neil Hansen, a plan to destroy London by fire. It did not succeed in the attempt to destroy London physically, but the repeated Gotha raids in 1917/1918 went some way to weakening the morale of the people and the disorganisation of city life. The night attacks caused a “Tendency of some sections of the population to give way to panic” which added to the chaos caused by physical damage.

An American engineer, albeit quoted by a Major Freiherr von Bülow, described his impression: “The air raids…. have aroused extraordinary fear among all sections of the population, Domestic servants have left their employers, the omnibus and tram drivers refuse to go on night duty and abandoned their vehicles as soon as the alarm sounded. The working classes, whose night’s rest is perpetually broken up, failed to go to work and schoolchildren had to be given permission to sleep in school hours.”

In January 1918 the Riesenflugzeugen, R-Planes or Giants joined in the raids on London and resumption of the attempt to drop enough incendiaries to cause serious damage to London and war production ensued. Due to lack of supplies of incendiaries and the failure to drop them in an enough concentration, this plan failed. The air defences of London had been strengthened by barrage balloons and steel curtains, forcing the attacking planes to an altitude too high to drop the incendiaries with any precision. On the last large Gotha raid at Whitsun 1918 RAF fighters shot down 7 planes and 3 more were claimed by anti-aircraft guns. German strategic bombing was then halted to support the Spring Offensive of the German army in March 1918.

Testing the courage of Londoners

The Gotha raids of 1917/18 has tested the courage and morale of Londoners severely, but had not resulted in large scale civil disobedience, major strikes or the paralysing of the city’s commerce. It is significant that the breaking of the city’s morale was a major aim, as the main targets for the air raids were the government buildings, the Admiralty, the Bank of England and Fleet Street.

The aerial bombardment of London in the Great War coloured inter-war governments’ attitudes to appeasement and the prospect of bombing in a future war, as Stanley Baldwin in 1932 predicted that “The bomber will always get through.” Practically, Londoners and the government had learned valuable lessons about the necessity for air raid precautions, the organisation of civil defence and the importance of the maintaining high morale or a “Blitz Spirit.”

General Ludendorff had described the aim of Germany in the bombing of London in the First World War as bringing the actual theatre of war to the capital of the enemy and to achieve the “moral intimidation of the British nation and the crippling of the will to fight”. This strategy had been continued into the Second World War with the Blitz in 1940/41 and the attack of the V1 flying bombs the Summer of 1944. At a press conference on 7 September Duncan Sandys, the minister in charge of dealing with the V1s announced “Except possibly for a few last shots, the Battle of London is over”.

The first ballistic missile attacks

The next day the first ballistic missile in history unleashed the death and destruction of the V2 rocket attacks. The rockets could not be tracked on radar and no warnings could be given. During the first 10 days of attack 25 rockets landed in England, 16 in London. The aim of the rockets improved and in the week ending 1 November 26 rockets had landed in London, increasingly among the built-up areas. The attacks lasted until March 1945. Casualties in the London region were 2,500 dead and 6,500 seriously injured, 1,700 who subsequently died. An example of a particularly horrific rocket attack was the incident at Woolworths at Deptford 25 November when 168 shoppers and passers-by were killed and 123 seriously injured.

Coming at the end of a war that many British people realised was nearly won, and hard on the heels of the V1 bombs, the V2 attacks understandably had a detrimental effect on morale. The approach of the rocket was unseen and unheard until a double bang announced that one had landed. The government at first imposed a blackout on any information on the rocket attacks, leaving the population to speculate on “flying gas mains”, although a home intelligence report made it clear that many people realised that the explosions were being caused by “a stratospheric shell which could devastate everything within a square mile.”

Several aspects of the attacks however ensured that morale did not reach unacceptable levels. Mass observation reported the development of a fatalistic attitude to the fact that no warning could be given or precautions taken. A sense of solidarity as engendered by the fact the rockets fell on rich and poor alike. Although the effect on the bombs was devastating, the civil defence services did magnificent work in dealing with incidents and saving lives of trapped victims. It was estimated that 20,000 Londoners owed their lives to this rescue work. The organisation of sheltering in the underground tube system was much more organised than in 1917, or even in the blitz of 1940.

As was discovered by the British War Cabinet when bombing large German cities devastating aerial attacks do not necessarily cause a significant drop in morale of the civilian population, but the V2 rocket, if it had been ready and utilised earlier than the last months of the war would arguably have driven the long besieged Londoners to protest and unrest, as well as further weakening the physical structure of the capital. Further protest would surely have ensued if it had become common knowledge that the government had turned a blind eye to the activities of the intelligence service to deceive the enemy into aiming for south London instead of central London.

This article has dealt with the experiences of the effect of bombing on London. Following the Second World War and the nuclear bombing of Japan in 1945, aerial bombardment has become one of the preferred methods of attack throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. It has resulted in the deaths of millions of civilians and can be said to be the main way in which warfare is brought to the urban environment.

Sources

Primary Sources

House of Commons Debates: Vol 95 June 1917

The National Archives

AIR 20/2652

AIR 20/06/2017

CAB 46

CAB 121/215

CAB154/49

H0 199/375 Press Cuttings,

HO 186/2299

Home Intelligence Reports nos 220 and 215.

Newspapers :

The Times 1917-1945

Secondary Sources including articles:

Emmerson, Charles. 1913: The World Before the Great War (London: Vintage ,2013).

Douhet, Giulio. Command of the Air (1921),

Angus Calder. The Myth of the Blitz (London: Jonathan Cape,1989).

Campbell, Christy. Target London: Under Attack from V-Weapons during WW11

(London: Little Brown,2012).

Collier, Basil. History of the Second World War, The Defence of the Kingdom (London: HMSO, 1957)

Gardiner, Juliet. Wartime Britain 1939-1945 (London: Headline Books).

Hansen, Neil. First Blitz: The secret Plan to Raze London to the Ground in 1918 (London: Corgi, 2008)

Hermiston, Roger. All Behind You, Winston: Churchill’s Great Coalition 1940-45 (London: Aurum Press, 2016),

Jones, Edgar. “Air Raids and the Crowd: Citizens at War”, The Psychologist Vol.29, No 6, 2016.

O’ Brien T.H. Civil Defence (London: HMSO ,1955).

Parker, Nigel. Gott Strafe England: The German Assault against Great Britain 1914-18, Vol 1 (Solihull: Helion, 2015).

Mackay, R. Half the Battle – Civilian Morale during the Second World War (Manchester: 2002).

Marwick, Arthur. The Home Front, The British and the Second World War (London: Thomas and Hudson, 1976).

Morrison, Frank. War on Great Cities, A Study of the Facts (London: Faber and Faber, 1937).

Waller, Maureen. London 1945 (London: John Murray, 2004).

White, Jerry. Zeppelin Nights: London and the First World War (London: Vintage,2015).

Zeigler, Philip. London at War (London: Sinclair Stevenson).

Websites :

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwtwo/ff3_blitz.shtml. (consulted May 3,2019)

Copyright © 2020 linda-parker.co.uk – All Rights Reserved